Down to clown in Venice

I began indulging my love for harlequin motifs with my Junco Sweater, but at the end of last month, I got to visit the harlequin homeland: Italy!

My partner, who is a freelance assistant camera operator, worked on Cover-Up, a documentary about journalist Seymour Hersh and directed by Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus. He was invited to attend its premiere at the Venice Film Festival, and I got to go with!

This event was wild. Most of the time, I felt like I had snuck into the back door of a party I hadn’t been invited to. My partner noticed Mads Mikkelsen and was tempted to tell him how much he enjoyed his work in Death Stranding. I accidentally caught Tilda Swinton on camera trying to film an art installation. Willem Dafoe was hanging out in the hotel bar. I drank Negronis while watching people I can only assume were European royalty pass by in evening gowns. Guards walked around wearing military berets and machine guns. I was nervous to make sudden moves.

The level of wealth was strange to me. It was strange to witness in person. It was especially strange considering that Cover-Up is about a guy who blew the top off multiple war crimes committed by American’s military, namely, the My Lai massacre during the US invasion of Vietnam, and the torture at Abu Ghraib prison during the invasion of Iraq. Hersh is a truly remarkable person who pursues the truth regardless of what people think, and what enemies he makes. He’s been accused of spreading conspiracy theories. He was the subject of angry, worried phone calls between Nixon and Kissinger. He’s on the left in this photo from Reuters.

The same day Cover-Up premiered, so did After the Hunt, a new Luca Guadagnino movie starring Julia Roberts and Ayo Edebiri. We passed the red carpet during their entrance but couldn’t see over the wall of photographers. But I do wish I had seen Roberts’s dress with my own eyes:

Roberts wore Atelier Versace, a long blue-black gown with a low-contrast pattern of diamonds cascading down the skirt and rising up the shoulders. I thought this was a fashionable nod to the history of comedia dell’arte and Harlequin in its country of origin.

In commedia dell’arte theater, Harlequin is a stock character, a servant and a trickster with two masters, undermining the authority of both. Which is also why Harley Quinn of DC comics makes such a good anti-hero: sometimes allied with the abusive Joker and sometimes Batman, she flips between her penchant for chaos and her moral agency.

Harlequin’s costume patterns range from diamonds to patchwork triangles, often colorful and bright, but sometimes black and red. And in Venice, those motifs manifest in Carnevale masks. As a former Catholic, I still feel drawn to the gilded imagery of Catholic religious ritual, and the way it has adapted (or appropriated, in many cases) pagan traditions. It’s catnip to a heathen like me.

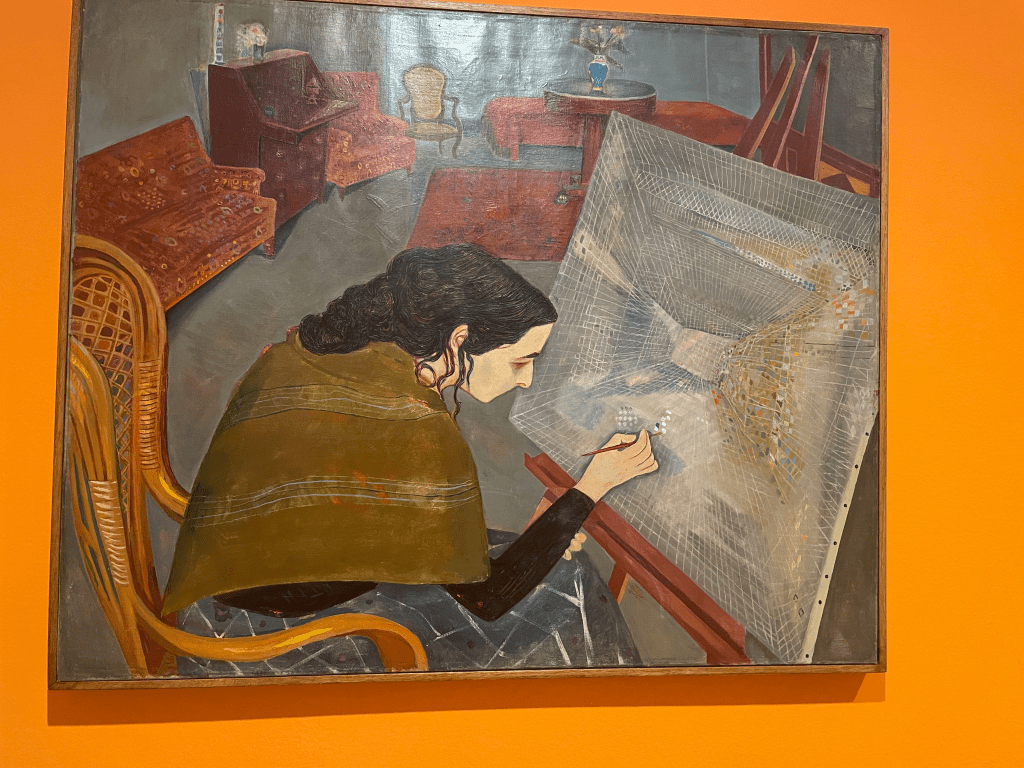

I also got to visit the Peggy Guggenheim collection, where they happened to have a temporary exhibit featuring the work of Helena Maria Vieira da Silva, a Portuguese abstract painter who mapped space using grids of colorful squares. I was really taken by this exhibit and Vieira da Silva’s style, and I think it’s no coincidence that she also worked in tapestry and stained glass – the way those forms naturally lead toward geometry, pixelation, and abstraction probably had an influence on her painting style, the signature use of a grid to create depth and find form in her depictions of movement, cityscapes, and interiors.

Now that I’m back from Venice, I’ve been looking for ways to translate that interest in diamond motifs into knitwear. Through my searches on Ravelry, I came across this project by user SilasM.

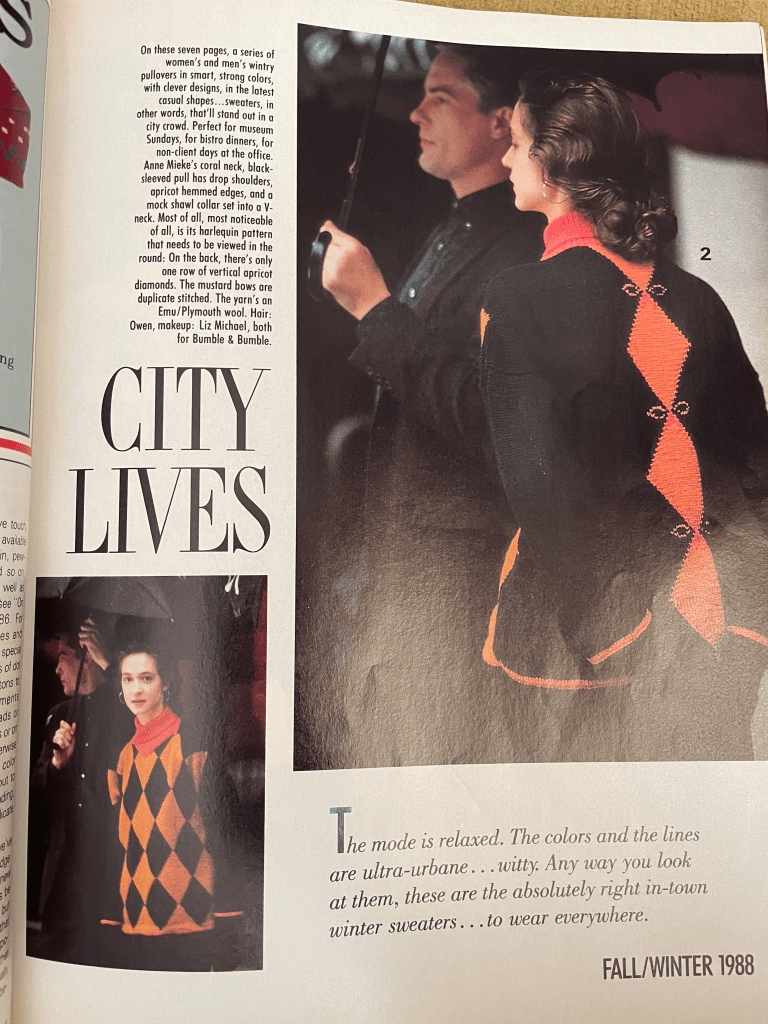

That was it, that was exactly what I wanted to make. The pattern is Harlequin Pullover by Anne Mieke Louwerens, an artist who has worked in textiles and knitwear design, painting, graphic design, and ceramics.

But I had a small roadblock. I couldn’t find this pattern online anywhere, because it was originally published in the fall/winter 1988 issue of Vogue Knitting.

But that’s why God made eBay, right? Luckily I found a hard copy of the issue from a seller on the site, who kept this magazine miraculously preserved for the last 36 years.

After looking at the pattern directions, I’m already planning a couple mods. To feel truly in the piebald spirit of Harlequin, I want to make all the contrast color diamonds different colors. I’m also planning to add some shoulder shaping, and sleeve decreases to preserve some yardage. I’m split on the cowl neck. I love how it looks, but I’m partial to lower necklines. It’s added by picking up the stitches around the neck after the rest of the sweater pieces are grafted together, so I won’t have to make a decision until much, much later.

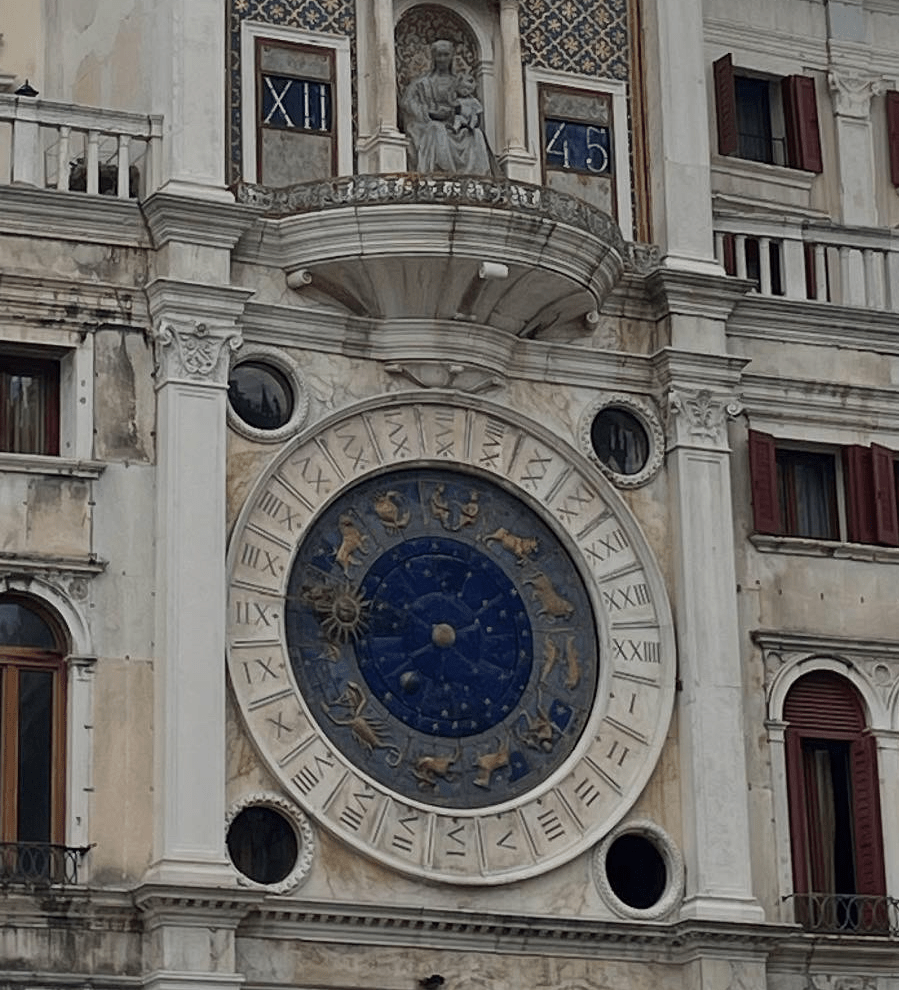

The diamond motif wasn’t the only thing that caught my eye in Venice. Right now I’m also enamored with celestial imagery, which is all over the city (and other parts of Italy, according to my friend who has traveled more extensively there). So I was completely transfixed by the Torre dell’Orologio in San Marco Square, an astronomical clock tower depicting the 12 zodiac signs. It tells the time, and the positions of the moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, as well as the astrological position of the sun.

I also found plenty of inspiration in the tile floors at San Giorgio, a church and monastery. The island, San Giorgio Maggiore, is also home to a photography gallery, which had an exhibit on Robert Mapplethorpe while we visited.

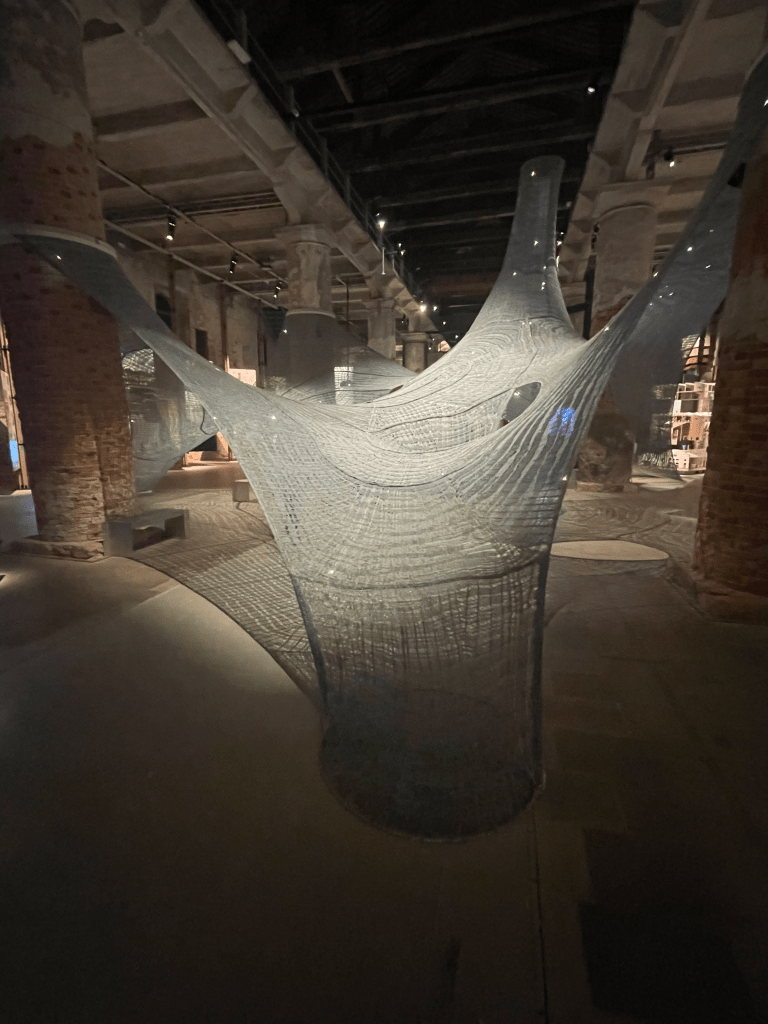

In addition to Venice’s classic sights, we were invited by the Cover-Up production team to the Biennale Architetturra to see the installation “Calculating Empires” by Kate Crawford, a researcher who has been studying AI for the past decade, and artist Vladen Joler. I got to speak a little with Dr. Crawford, who was so extremely cool. The project is available to view online here.

Also at the Biennale Architetturra was Necto, an installation made from knit fiber and LED lights. Read the full details here.

And besides the “official” art, there were tons of murals and graffiti all around Venice. Much of it was anti-Amazon and anti-Bezos, since he had just completely shut down the city for his own wedding just a few months prior. Most of it was in support of a free Palestine and an end to the genocide in Gaza.

And last, the two funniest images I took. On the left, a young man whose whole job is to carry a falcon around to scare pigeons away from this rooftop bar. On the right, a trio of suited, ear wire-wearing tough guy security guards at the Film Festival take a much-needed gelato break.

There are worse gigs, probably.