Reckoning with the pussy hat and engaging with art activism in Trump’s second term

I want to talk about a customer I met when I worked at the yarn store. She was telling about a project that she was working on, or recently finished, I can’t remember. It was a stranded colorwork hat that spelled “Fuck Trump” in morse code. It was hard for me to stop myself from saying that this was useless.

Who was it for? Who was she signaling to? How many people on the street know morse code? This is emblematic to me of a snickering cosplay mischief that many white liberals find themselves employing with a hashtag resistance. I remember thinking “At least spell out Fuck Trump in plain English. The least you could do is get in an actual confrontation.” But how would she feel like a Katniss Everdeen or a Hermione Granger, forced to use code and subterfuge under an imagined threat of censorship? Because of course, no one would question her right to free speech or citizenship, or mine.

Years later during Trump’s second term, it’s Black and Brown people, Muslims, immigrants both documented and undocumented who are targeted for writing about and protesting genocide. Mahmoud Khalil, Rumeysa Ozturk, and more since I’ve started writing this post have been disappeared by agents, or had their green cards suddenly voided by Trump’s government. Two planes’ worth of people were flown to CECOT prison in El Salvador under suspicion of being in a gang, without due process or evidence other than having tattoos. They were used as set dressing by Kristi Noem, looking lovely with her hair extensions, designer jewelry, and fillers in the middle of a prison. She’s allowed these feminizing procedures and accessories, of course, because she was born with a vagina, unlike the incarcerated trans women who have been sent to men’s prisons over the past several months. Us cis women can have all the gender affirmation we want.

Both during Trump’s first administration and now, crafters have loved to point to times when crafts were used to subvert fascism and oppression – anti-Nazi resistance spies carrying messages encoded in knitting patterns, for instance, or the more obscure history of Black and allied quilters using specific patterns or colors to signal to people escaping slavery on the Underground Railroad. The pussy hat of 2017 was an attempt to pay homage to the interesting ways “women’s work” was used for good and to unite crafters as a community against Trumpian fascism. It was a flashpoint that drew media attention to knitting and crochet: criticism from the right that I will not entertain, and earned criticism from the left for its dominating presence at the Women’s March without the leadership or input of Black and trans women.

I didn’t wear a pussy hat that day. I did, however, carry a sign that said “pussy grabs back” and depicted a vulva as a bear trap. I, like a lot of other cis and white feminists, were directly responding to Trump’s “grab ’em by the pussy” line and the shameless joy he took in the sexual assault of cis women. Cis women felt attacked. It was an attack. But then our response to this attack swallowed every other way Trump was attacking marginalized people. The pink pussy hat and its symbolism became a black hole, spaghettifying all other insights, experiences, and needs in that moment. It’s true that there was immense fervor for the image of thousands of women wearing pink pussy hats. It’s also true that the kind of person who wears one is the kind of person the media is more likely to pay attention to. I also think it was very emblematic of the way knitters tend to “build community”: through sameness and FOMO.

Obviously knitting is important to us, so when it has a big global moment, we want to be involved. When the Women’s March was being planned, it attracted many people who had never been to a march or protest in their life, which is a success. And a lot of freshly enraged knitting people saw the pussy hat project and thought, “here is another way for me to belong in this movement, with other people with this same skill”. And then the pussy hat attracted people who didn’t knit or crochet, but got their pussy hats from donation stations set up at yarn shops or from crafting friends. Maybe these non-crafty enraged people saw the media attention around the pussy hat and thought, “hey, maybe I should try this too.” A success for knitting, but what about for organizing?

I see the popularity of the pussy hat, and the avenues used to popularize it, as the same as any other hit knitting pattern. It was being made by many big-name designers, whose orbits of fans then made their own. KALs and CALs were organized, and how could we miss out on that? About a year and half after the Women’s March is when I got my job in the yarn business, and I saw the same enthusiasm for the pussy hat applying to so many other patterns and designers. The same dozen or so designers on the first page of Ravelry’s “Hot Right Now” search; hundreds of people gathered on the hill at Rhinebeck in the same sweater. There’s a commonality created by a shared art and interest, but not necessarily community.

The pussy hat, or any handmade object, can’t accomplish what its creators wanted: solidarity. People have to do that. An object a just a symbol, and a symbol has to stand for something that already exists. In that way, the pussy hat was the cart placed before the horse.

I am not writing off crafting’s potential for community-building. But stitches alone don’t foster solidarity, and knitting communities are just as good at excluding as including. Black yarn crafters have frequently reported being followed in yarn shops, a problem of racist profiling common across the retail industry, or just treated as though they don’t know what they’re doing. Ruth Terry’s article “Black People Were the Original Craftivists” points out the harsh irony that white Americans exploited the textile expertise of enslaved people, just to push their descendants from craft spaces once knitting and sewing became leisure activities after WWII. A meaningful resistance movement in crafting, or any discourse, cannot be fomented without direct, vocal anti-racism. There are a lot of crafters willing to ignore racism, or any criticism levied against them about race, for the illusion of unity.

Another problem with trying to publicly proclaim crafters as the resistance is that we are largely not. There are plenty of highly traditional “alpha males” who might see me knitting and agree that’s what I should be doing with my time because I’m a woman. They might assume that I am interested in a narrow role of homemaking and motherhood because knitting is symbolic of “good old days” that never really existed. They might assume I share values of gender essentialism, natalism, patriarchy, and white supremacy. And there are certainly women who knit who do share those values.

I notice the incredible spectrum people at fiber festivals: the highly conservative women and their husbands, the visibly queer, the feminists who feel artistic pride in “women’s work”, rural livestock farmers who symbolize a pastoral America, even as the country becomes increasingly hostile to their livelihoods. Don’t forget, too, that agriculture in this country is hugely supported by immigrants’ intense labor. Fiber festivals have an amazing ability to pull all these different people together based on a shared interest/hobby/career/trade. To actually build solidarity there, I return to my thoughts on the morse code Fuck Trump hat: we need to use our words.

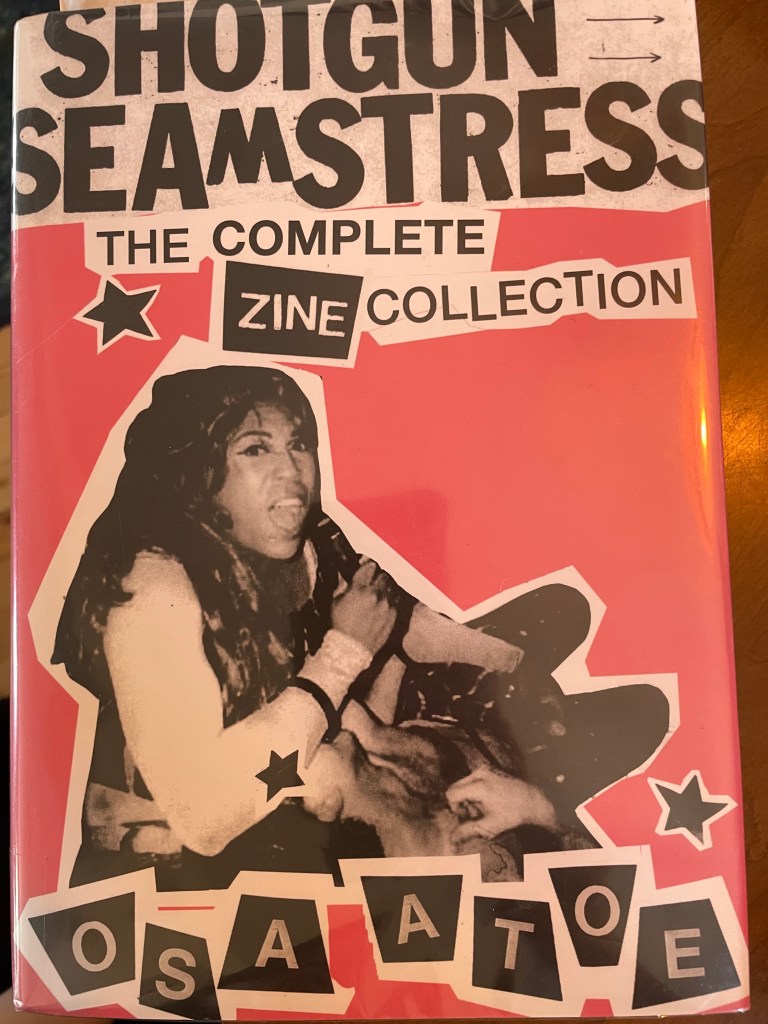

I was sounding out my ideas for this blog post with a friend, about how crafting can create community, or if it even can. They suggested I look outside of fiber to zines, and I have found zine culture to be particularly inspiring. While zines exist in many scenes and for many reasons (sharing creative writing, art, comics, political manifestos) they’re probably most heavily associated with punk and riot grrl subculture. Zines are works of art in themselves that also take advantage of art-centered gatherings for dissemination. I wrote about Shotgun Seamstress a few weeks ago, a zine started by musician and artist Osa Atoe to platform and unify other Black punks and musicians. The scene existed, but Atoe was tired of punk being presented as a largely white subculture, and therefore fraught with racism and implicit bias against Black musicians and fans. Just being at the shows and enjoying the music isn’t enough for a strong community – ideas and the leadership of the most marginalized are essential for creating the solidarity left-leaning crafters want to celebrate. Zines can be an excellent model for idea-sharing in the fiber world, a way to make the most of packed gatherings of fiber crafters to find new coalitions and allies.

This is why my post is so front-packed with the issues that are crucial to me and my friends at this moment, and why I don’t see fiber crafts, this thing that brings me so much joy, as an escape from the worries of the world. The phrase “stick to knitting” doesn’t just feel condescending, it feels impossible. I can’t extract anything I love doing from who I am or what I believe in. So when I enter fiber festivals, knitting/crochet/quilting/sewing circles, yarn stores, craft guilds, I want to make it 100% clear where I stand and who I want to unite with.